Anxiety and stress plague temporary foreign workers

A pilot study underscores mental health strain as the greatest burden temporary foreign workers carry, caused by the changes to Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program.

In a study entitled “Interrogating the Impact of Recent Changes to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program to Temporary Foreign Workers in Alberta,” researchers at the University of Alberta found that high level of anxiety and poor mental health are evident in TFWs who are affected by the changes.

The study was released on March 18 by researchers from UoA, York University, University of Sydney, in collaboration with non-government organizations, reported the Inquirer.

It was disseminated to stakeholders including members of the provincial and parliament of Canada, settlement services and policy makers, researchers said.

Thirty-five TFWs living in rural and urban areas in Alberta participated in focus group discussions in August, September and November 2015.

The participants, mainly from the low-skilled category such as fas food and gas retail attendants, were from the Philippines, India, Nepal, Jamaica and Bangladesh.

The researchers used a critical qualitative approach in collecting data and NVivo 10 qualitative data analysis software to interpret data.

Analysis of the focus group discussions indicates that many of the participants continuously suffer from anxiety and stress “due to the demands placed upon them by their work and immigration statuses.”

A worker said, “It is really stressful because you are thinking, what is going to happen tomorrow, what is going to happen the next day. You can’t make any decisions.”

The study notes that although TFWs admit their mental health was poor, the need to provide for their family and precarious migration status got in the way of addressing issues related to mental health.

“Temporary foreign workers seem to be interminably waiting – for applications to process while others expire – which leaves them in a constant state of anxiety,” the researchers note.

The stigma in seeking help for mental health and emotional wellbeing prevents TFWs from accessing support services and is an uncommon practice in their cultures.

Integrating within their own communities is a way to cope, according to the participants.

A participant said, “My friend, he called me, like, last week it happened, he called me at midnight and he started crying..[he said], could you please come and visit me and…then I have to take a cab and go to his place, like, you know, have a good chat, make him feel comfortable.”

For some, simple lack of knowledge and having no time to access services are the main barriers.

Rapid changes, often without adequate warning to foreign workers, have become a key feature of the TFW program, the study states.

The changes that came into effect in 2014 under the TFW program made it tougher for employers to hire TFWs by being required a $1,000 fee, a progressive yearly reduction in TFWs staffing down to 10 percent this year and a no permit policy for areas that have 6 pecent unemployment rate.

It notes that some 70,000 TFWs had expired contracts in April 2015 when the “4-in, 4-out” rule came into force. The measure forced some TFWs to leave Canada and others risked staying as undocumented.

Based on its findings, the study makes some recommendations including recruiting a temporary foreign worker advocate in the province.

“This advocate must be able to develop relationships and trust with the most marginalized and vulnerable groups of temporary foreign workers,” it says.

The researchers are also proposing that a fund be funneled to a one-stop service provider for TFWs that would include legal support.

To aid in foreign workers’ stress and mental health, the study also supports open work permits for TFWs, which in turn would reduce cases of exploitation.

“The goal from the beginning was to conduct some form of participatory action research project to attend to the well being of TFWs in Alberta [with] a focus to conduct a small study that will inform the development of a larger study,” says Bukola Salami, lead investigator and Assistant Professor of Nursing at UoA.

Salami observes that while a study was being conducted in 2015 on the health of TFWs, the sector was being battered by several changes in the TFW program including the 4-in, 4-out rule.

“I was quite disturbed by the challenges stakeholders indicated that TFWs were experiencing and the systemic injustices related to this population,” she says.

“They are often treated in the systems as objects or tools for labor in Canada without a broader consideration of their lives and the lives of their families. As some of the participants indicated, we have a multi-layered hierarchy in terms of rights in Canada,” she adds.

Salami cites a statement from one of the participants who said:

“When I came here, I heard about Canada. [In] Canada the human rights is good but what I feel when I come here, there is nothing. Canada is good country, but they have also human rights for people who are permanent residents, not for us.”

Funding is being sought for a follow-up study from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to begin research in June 2017, Salami reports.

“We hope to conduct some form of participatory action research project that will improve the well being of TFWs and give them some basis of action to exercise their rights in Canada,” she adds.

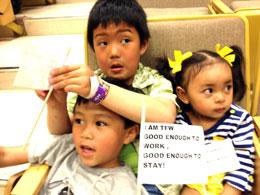

UFCW Canada, which represents more than a quarter of a million Canadian workers has also mounted a campaign saying if migrant workers are good enough to work in Canada, they are good enough to stay.